In my last post, I looked at a few different techniques using visual transformers architectures to create representations of my photography. In particular, using DINOv2. August was a very busy travel month for me. I had the time to do a lot of new photography, including in my home city of Austin. This inspired me to “app-ify” the results of Part 1 so I can explore my photography more easily and decide what photos to edit. Rapid prototyping of applications is extremely valuable for young data scientists to learn. This blog shows off some cool pictures and illustrate the process of designing this simple app. The code for this blog post is available here.

Design Decisions

Any good design process starts with asking what problem you’re trying to solve. In my case, I go out for a day of photography and will take anywhere from a couple hundred to a couple thousand photographs. On vacations, I can easily shoot over 10,000 photographs. The problem is most of them suck. I want to find the unique “moments” from the day and figure out which ones are worthy of being touched up in Adobe Lightroom.

With this problem statement, I have two main problems to solve. The first one I explored in Part 1, which is the identification of unique themes. I accomplished this by applying K-Means clustering to get a set of clusters that represent connected groups of photos. I saw that choosing a high number of clusters between 25-50% of the sample size yielded the highest quality clusters. This gives rise to the second problem. There is still room for substantial variability within some clusters, and randomly selecting a cluster member doesn’t let me efficiently pick the best photo for editing.

With the solution in Part 1, I had no control over what my sample image from each cluster was. It could have been the worst shot of that particular point in the day, but an amazing shot is that image’s closest neighbor. In order to actually explore the moments from throughout the day in detail, I want to be able to explore the image space near a particular cluster representative.

Here lies the main problem this application needs to overcome. Calculating all pairwise distances between the DINOv2 embeddings for large amounts of imagery is prohibitively slow for large numbers of images. I need a way to make querying the distances between images efficient. Fortunately, a class of databases that spatially index and optimize vectors for lookup exist and I can easily use an existing solution for indexing my photos.

The last set of considerations I made in the design process are about the app’s intended audience. I am going to interact with it as a web application in my browser and run it on my local machine. This means I don’t have to worry about horizontal scaling of the DINOv2 model due to a sudden surge of API requests from strangers. In fact, entire companies in the MLOps space (including my own) worry about what to do if you need to worry about this, so I’ll just shamelessly plug Striveworks’ Chariot Platform. For the core application, I use Gradio, an awesome tool to declaratively create interactive UIs in Python (in case you are JavaScript-challenged like me).

Gradio App Outline

Here is an outline of the application I built with the implementation details left off for the event listeners.

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Load configuration from JSON file passed via command line

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("Usage: python deno.py <config.json>")

sys.exit(1)

config_path = sys.argv[1]

config = load_config(config_path)

# Initialize PostgreSQL with pgvector

initialize_pgvector(config)

# Gradio Interface

with gr.Blocks() as demo:

gr.Markdown("# Image Exploration Application")

gr.Markdown(

"Use AI to explore the unique points in your image gallery and find high quality photos."

)

gr.Markdown("## Usage")

gr.Markdown(

"""

Simply upload a folder with your images. Resize beforehand for best results. After upload, the

images will be processed and unique moments will be entered into the gallery on the right. Select

an image to populate the bottom gallery with similar images. To reset the application, simply

press reset on the bottom row and clear the upload box. To re-run with the same uploaded images

and a different granularity, press the reprocess button after resetting the application.

"""

)

gr.Markdown("## Granularity Slider")

gr.Markdown("The ratio of unique moments to total images.")

with gr.Row():

granularity_slider = gr.Slider(

minimum=0, maximum=1, step=0.01, value=0.5, label="Granularity"

)

with gr.Row():

image_input = gr.Files(

type="filepath",

file_count="directory",

label="Upload Files",

height=512,

)

gallery = gr.Gallery(label="Cluster Centers")

with gr.Row():

similar_images_gallery = gr.Gallery()

with gr.Row():

reset_button = gr.Button("Reset")

with gr.Row():

reprocess_button = gr.Button("Reprocess")

image_input.upload(

fn=update_gallery,

inputs=[image_input, granularity_slider],

outputs=gallery,

show_progress="full",

concurrency_limit=10,

)

reprocess_button.click(

fn=reprocess_gallery,

inputs=[image_input, granularity_slider],

outputs=gallery,

show_progress=True,

)

gallery.select(

fn=display_similar_images, inputs=None, outputs=similar_images_gallery

)

reset_button.click(

fn=reset_application,

inputs=None,

outputs=[gallery, similar_images_gallery, granularity_slider],

)

# Set share to False if running containerized

demo.launch(server_name="0.0.0.0", server_port=7860, share=True)

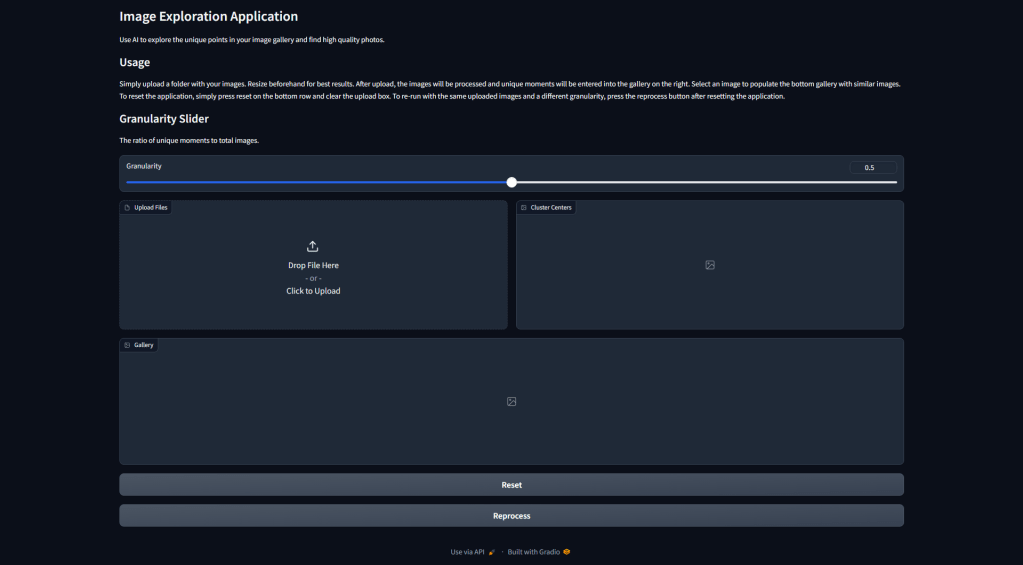

If we run the application, we will see each of the components rendered.

Walking through the components of Figure 1 as they exist in the code, we have:

- Some Markdown describing what the application is and how to use this.

- A granularity slider that tells the application how many cluster centroids to display in the gallery on the right.

- An upload folder box.

- A gallery that will hold the cluster example images.

- A gallery that will hold 10 nearby images when a cluster center is clicked.

- A button to reset the clustering calculation.

- A button to reprocess the clusters with a new granularity.

Gradio handles events in the UI by defining listener functions that take in Gradio components as input and write output accordingly. In the code presented, you can see that I have done this for the gallery uploads and selects. The image processing portion of the application that creates the DINOv2 vectors is in the Github code, but essentially follows the same logic as Part 1 of this blog and uses the mean-aggregated vectors. Read that post if you want to understand that piece!

Vector Database

With the core of the application defined, let’s talk about what I do with these vectors once they’re created. Vector databases are used to rapidly use a vector to query a collection of vectors for similarity. For this reason, they have recently become popular components of retrieval augmented regression (RAG) workflows using LLMs. Johnson et al. 2017 presents an early example of the underlying query mechanisms present in modern vector database solutions like Milvus, pgvector, and Pinecone. For my project, I use pgvector because it’s built on top of PostgreSQL and I can build a simple database model in SQLAlchemy. SQLAlchemy creates database tables by defining a model, like this one:

from sqlalchemy import (

Column,

Integer,

String,

)

from pgvector.sqlalchemy import Vector

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

Base = declarative_base()

class ImageEmbedding(Base):

__tablename__ = "image_embeddings"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True)

image_path = Column(String, unique=True, nullable=False)

embedding = Column(Vector(1024))

Here, I have created a table with a column that stores the image path on the server along with an embedding column. The dimension is set to 1024 to take the DINOv2 Large model embeddings. To actually use this, we have to remember to enable the vector extension in our database. I’ll leave my initialization logic here, which wipes the database on application restart, as an example of how to configure this in a Python application with SQLAlchemy.

def initialize_pgvector(config: dict):

"""

Initialize the connection to the PostgreSQL database with SQLAlchemy.

Parameters

----------

config : dict

PostgreSQL configuration settings.

"""

global Session, engine

db_url = f"postgresql+psycopg2://{config['postgresql']['user']}:{config['postgresql']['password']}@{config['postgresql']['host']}:{config['postgresql']['port']}/{config['postgresql']['database']}"

engine = create_engine(db_url)

# Create a configured "Session" class

Session = sessionmaker(bind=engine)

# Clear existing data

clear_database(hard_delete=config.get("hard_delete") or True)

# Create the table for storing image embeddings if it doesn't exist

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

# Create the vector extension

with Session() as session:

with session.begin():

session.execute(text("CREATE EXTENSION IF NOT EXISTS VECTOR;"))

In my application, the database is initially populated with vectors, and then nearby vectors can be searched easily by their L2 distance.

def display_similar_images(selection: gr.SelectData) -> List[str]:

"""

Display the top 10 most similar images from PostgreSQL based on the selected image.

Parameters

----------

selection : gr.SelectData

The selection determined by the gradio state at the time

this function is called.

Returns

-------

List[str]

A list of paths to the top 10 similar images.

"""

session = Session()

image_path = selection.value["image"]["path"]

query_embedding = (

session.query(ImageEmbedding).filter_by(image_path=image_path).first().embedding

)

# Use the SQLAlchemy l2 vector similarity query (assuming pgvector extension)

similar_images = (

session.query(

ImageEmbedding,

ImageEmbedding.embedding.l2_distance(query_embedding).label("distance"),

)

.order_by("distance")

.limit(10)

.all()

)

similar_image_paths = [x[0].image_path for x in similar_images]

session.close()

return similar_image_paths

This method is what populates the bottom gallery described in the app layout and shown in Figure 1. One final note is that the lookup speed can be further optimized by applying a trained index to the vector database, such as IVFFlat which first partitions the space into clusters. These can be used in a two-stage lookup approach. I refer to Johnson et al. 2017 and the pgvector documentation for detailed explanations, but I don’t make these optimizations in this simple application.

Exploring Zilker Park and Downtown Austin

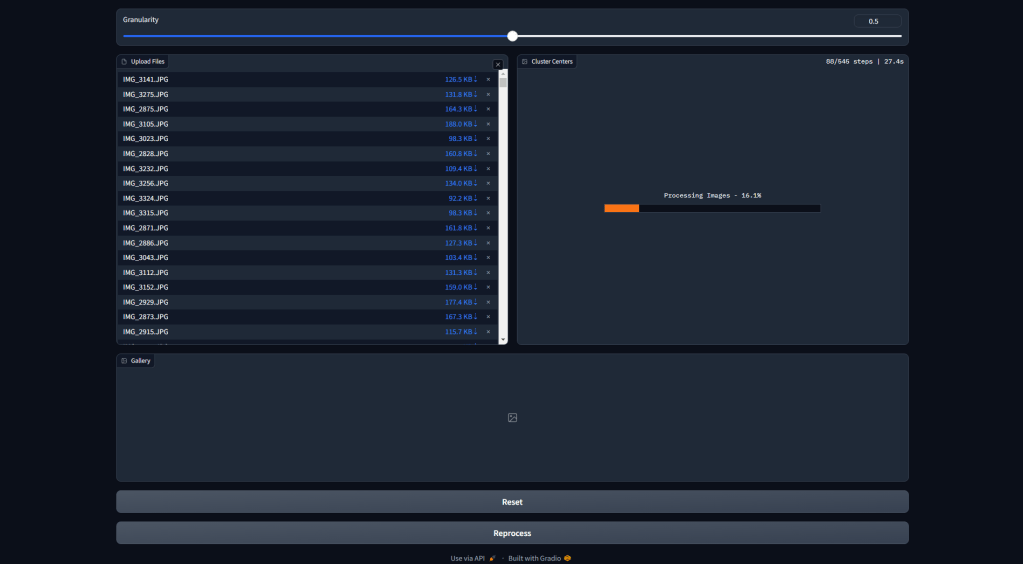

With the application and its components specified, I’m excited to show off some of the results of my photography session! For starters, I am starting from 545 6240 x 4160 JPEG images (keeping the RAW files for editing). These are taken from areas around Zilker Park, Barton Springs, and 6th St in downtown Austin throughout various points in the day. Because DINOv2 is going to resize this down to a shortest edge of 518 anyways, I’ just kept things simple and resized my images down 90% on each axis to speed up processing. I used this bash command to do the resizing (thanks ChatGPT):

src_dir="original_folder_name" && dest_dir="${src_dir}_resized" && mkdir -p "$dest_dir" && find "$src_dir" -type f -exec sh -c 'convert "$1" -resize 10% "$2/$(basename "$1")"' _ {} "$dest_dir" \;From the resized image directory, I uploaded the images through the interface.

In Figure 2, the processing stage is shown. The images are being run through the model and approximately 290 clusters are being generated.

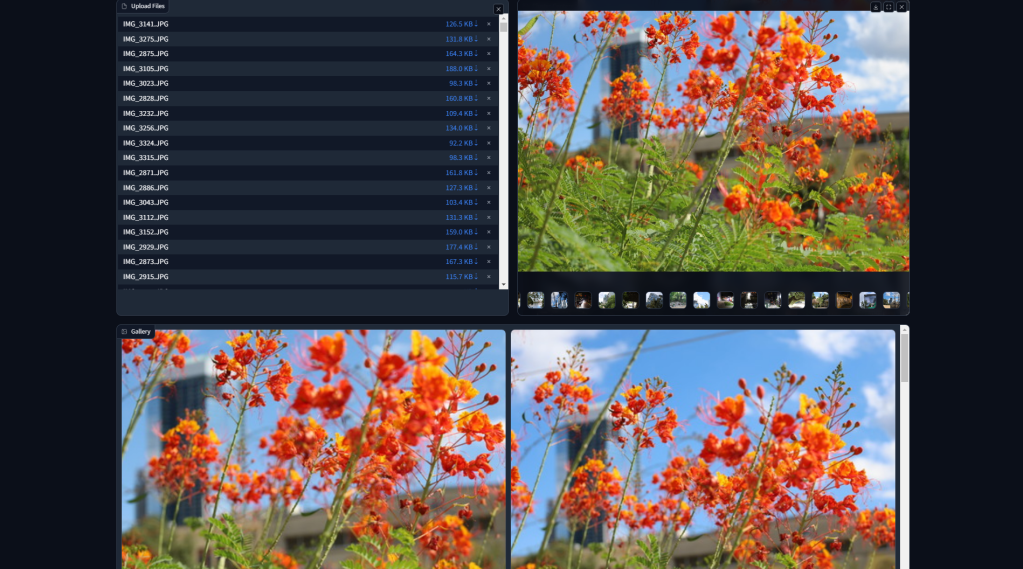

Once this is done, the right gallery populates. Selecting an image from the gallery populates the bottom gallery with the top 10 most similar images. This is shown in Figure 3. Obviously, we would expect the shots of the same set of flowers to be close to each other, but I continue to be impressed with the semantic understanding contained in foundational models like DINOv2.

Take the images grouped together in Figure 4. These are close in the DINOv2 embedding space, but have vastly different colors. The model is clearly understanding the semantic concept of “presence of graffiti”. This provides a very methodical way of filtering through large volumes of imagery by semantic content. Doing this allowed me to very quickly build a subset of images to edit in Adobe Lightroom representing some unique moments throughout the day.

Figure 5 shows some of my favorites that I went on to identify and edit in the span of about 30 minutes. Again, this represents a diverse sample throughout the day, and easily let me summarize my weekend to people who I told about this trip.

Thoughts and Conclusions

Once again, I am impressed with the semantic understanding of foundational vision models. Additionally, it is really satisfying to see a state of the art model running off my laptop to make my life easier. While none of what I did in this post is groundbreaking, I stand on the statement that application building is a skill all data scientists should practice. It’s easy to get siloed in R&D and academic benchmarks and forget the real world applicability of this emerging technology.

Because I am running this application locally for my benefit, this is the extent of what I will likely do to productionize. There’s a work in progress Dockerfile and docker-compose.yml on the Github repo to deploy this application, so feel free to steal it and hook it up to nginx if your needs differ.

As always, I welcome any engagement on the post. Next month, I am going to pivot away from computer vision for a bit, likely to talk about some applications of ML in my original academic field of astrophysics.

References

- Bauer, Jacob. “Vision Transformers Down Memory Lane (Part 1).” Jake’s Blog (blog), August 1, 2024. https://nazo.ai/2024/08/01/vision-transformers-down-memory-lane-part-1/.

- Oquab, Maxime, Timothée Darcet, Théo Moutakanni, Huy Vo, Marc Szafraniec, Vasil Khalidov, Pierre Fernandez, et al. “DINOv2: Learning Robust Visual Features without Supervision.” arXiv, February 2, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.07193.

- “Striveworks | The Chariot Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) Platform.” Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.striveworks.com/platform.

- Abid, Abubakar, Ali Abdalla, Ali Abid, Dawood Khan, Abdulrahman Alfozan, and James Zou. “Gradio: Hassle-Free Sharing and Testing of ML Models in the Wild.” Python, June 2019. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.02569.

- Johnson, Jeff, Matthijs Douze, and Hervé Jégou. “Billion-Scale Similarity Search with GPUs.” arXiv, 2017. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1702.08734.

- “Pgvector/Pgvector.” C. 2021. Reprint, pgvector, September 3, 2024. https://github.com/pgvector/pgvector.

Leave a comment